Key Takeaways

- Credit default swaps (CDS) are derivative instruments that allow investors to hedge against the risk of default on debt instruments.

- A CDS is like an insurance contract in the sense that it requires ongoing payments to the CDS seller in exchange for protection against a credit event (i.e. a default on a debt instrument).

- Michael Burry bought CDS on mortgage-backed securities and profited when people stopped paying their mortgages during the GFC.

100x With CDS

Popularised by the book and its movie adaptation ‘The Big Short’, Michael Burry’s bet against the housing market has become one of the most famous trades in history. The manager of Scion Capital earned around $800 million at the onset of the Great Financial Crisis. More recently, Bill Ackman of Pershing Square turned $27 million into $2.6 billion during the Covid crash of 2020, a 100-fold return. How did they do it? By using credit default swaps. These are derivative instruments that provide insurance against default or non-payment of debt obligations. That’s a mouthful, so let’s break it down.

Resemblance to insurance

The simplest way to understand credit default swaps is to compare them to insurance. Imagine that an investor, let’s call him Michael, buys a house and is worried about it burning down in a fire. Michael will pay a premium to an insurer every period. If the house burns down, the insurer will pay Michael his insurance claim (i.e. they will give him the pre-agreed sum of money to cover the damage from the fire). This way, Michael is transferring the risk of the fire to the insurer, and, in exchange for holding this risk, the insurer receives premium payments every period.

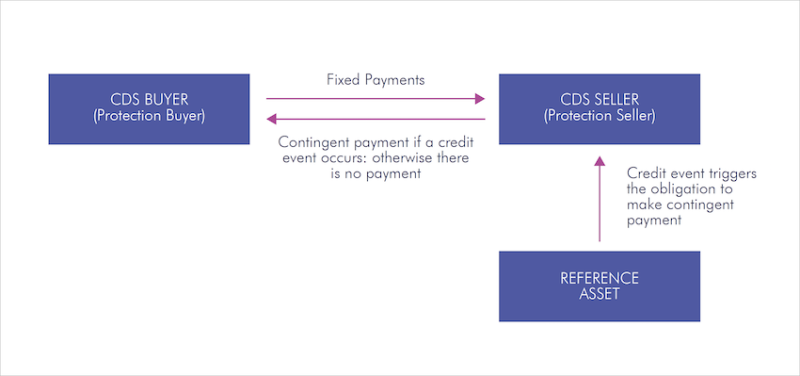

Similarly, a credit default swap (CDS) provides protection, not against fires, but against credit events. A credit event occurs when a borrower’s ability to pay its debt changes negatively and a default or restructure is necessary. For example, imagine Terrible Corp. issues bonds to raise capital and fund its operations. An investor, let’s call him Bill, thinks that Terrible Corp. will not be able to pay its debt holders. Hence, he will buy a CDS. This way, if Terrible Corp defaults, Bill will be protected and will receive payment from whoever sold him the CDS.

The comparison: the insurance buyer, Michael, purchases home insurance and if his house burns down the insurer will pay him whatever the claim dictates. The insurance company is willing to bear the fire risk because it will receive premiums every period, and as long as the house doesn’t burn down, they will keep collecting checks without having to pay out any claims. Likewise, the protection buyer, Bill, purchases a credit default swap. If Terrible Corp defaults on its debt, then the protection seller (i.e. whomever sold Bill the CDS) will pay him whatever the settlement amount is. The protection seller is willing to issue the contract because as long as Terrible Corp doesn’t default, they will have cash inflows from premiums but no cash outflows.

Source: GreenPoint Summit

Differences from insurance

Although insurance contracts and a CDS are comparable, there are some differences between the two. One key difference is that, with a typical insurance contract, the policyholder must be exposed to the insured risk. For example, if a person buys auto insurance, he often has to be the owner of the car. If there is an accident, the policyholder must be the one driving for the people in the car to be insured. Additional drivers can be added for a fee, but the policyholder will typically still be the vehicle owner.

Contrastingly, the person purchasing a CDS does not have to hold the debt that he is buying protection for. It’s like insuring someone else’s car. In the example above, Bill doesn’t have to own the bonds of Terrible Corp. Thus, a CDS allows traders to both hedge their risks and speculate on companies or countries that they expect to default on their debt.

Today, CDS contracts are traded in an over-the-counter market (i.e. bought directly from banks or other financial institutions). This is shown in a scene from The Big Short in which Burry approaches several banks and asks them to create a CDS. This is because he wanted to buy a CDS on mortgage-backed securities (MBS), but couldn’t find any financial institution selling these contracts in the market. Thus, the banks made the custom swap contracts on mortgage backed securities (MBS) and sold them to him. Let’s pause and rewind. What’s an MBS?

Mortgage-backed securities

An MBS is a security that is made up of other financial assets, specifically mortgages. This means that the cash flows of the MBS come from the cash flows of the mortgages that back it. For example, imagine that thousands of people go to a bank and take out a mortgage to buy a house. These thousands of mortgages are then pooled together. Then, the pool of loans is sold to an investment bank. This bank splits the pool into smaller units called tranches, which are determined based on the risk/return profile of the mortgages. These tranches are sold to investors. The investors holding the tranches receive the cash flows from the mortgages when the homeowners make their payments. This makes an MBS very much like a bond; the difference is that its much riskier for lower tranches because they only get paid after higher tranches, so not much will remain for them in case of default.

What Burry did was buy credit default swaps on these mortgage-backed securities (in finance terms, the MBS was the reference obligation of the CDS). Every period Burry would pay the banks their premiums, waiting for the MBS to go bust. Since the banks thought this wouldn’t happen, they were thrilled to sell the swaps to Burry. He was competing against the clock: if the credit event didn’t take place soon enough, he would run out of money due to the premiums. Eventually, homeowners became unable to meet their mortgage payments, meaning that the MBS would no longer provide cash flows to investors. This was the credit event that made the swaps that Burry held a lot more valuable: the swaps provided protection against mortgage defaults, so demand for them increased when people stopped paying their loans. This means they could either be sold to MBS owners who would need the settlement payments or be held to receive the claim (as in the “insurance payout”).

Credit default swaps vs traditional shorts

After all this, you might be wondering: why use a CDS instead of traditional shorting? For more information on short-selling you can read this article, but short-selling boils down to the following: an investor identifies an overvalued security, borrows it, sells it immediately, waits for the price to decrease, and then buys it back and returns the security. If an investor buys a CDS he will only lose the amount he must pay for the premiums (and the possible upfront payment for the CDS). Contrastingly, to close a short-sell investors must buy the shares again, even if the security’s price increases. Thus, they are exposed to unlimited losses. An additional advantage of a CDS is that the investor doesn’t need to own the reference obligation that the CDS is insuring, enabling investors to speculate.

Overall, credit default swaps (CDS) are derivative instruments that allow investors to hedge against the risk of default on debt instruments. They provide insurance in exchange for periodic payments. Apart from being a form of insurance, they enable investors like Burry Ackman to speculate on potential credit events.