Key Takeaways:

- The Digital Euro is being explored as a new form of central bank money to preserve monetary sovereignty as cash use declines and payment infrastructures remain dominated by private and foreign actors.

- It would coexist with cash and provide a public, low-cost digital payment option, reducing dependence on Visa/Mastercard and enhancing competition, interoperability, and European financial autonomy.

- A Digital Euro could strengthen monetary policy transmission, lower transaction costs, and support fintech development while potentially elevating the euro’s role in global payments if made interoperable with other CBDCs.

- Risks include privacy concerns, high implementation and transition costs, and destabilisation of bank funding if deposits shift into CBDC balances, risks the ECB aims to mitigate with deposit caps (€3–4k) and non-interest remuneration.

- Political acceptance, public trust, and transparent governance will determine its success; the project sits at the intersection of monetary strategy, technological design, and democratic legitimacy.

Over the past 25 years, the European Union has achieved remarkable financial integration through the creation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the introduction of the euro. These milestones are widely celebrated for reducing trade costs, streamlining cross-border payments, enhancing competitiveness, and strengthening European economic sovereignty. Yet, the nature of money itself continues to evolve, and Europe’s financial integration remains incomplete.

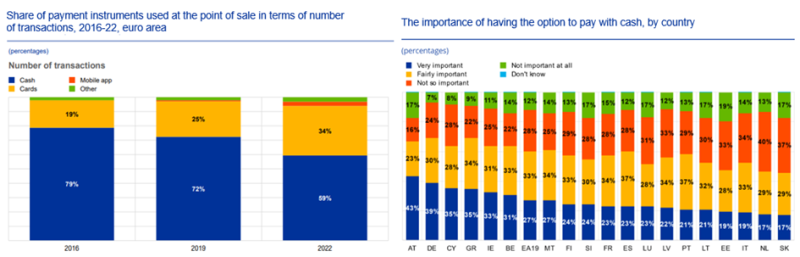

The European payment landscape is still fragmented, with national banking systems and foreign payment networks, most notably Visa and Mastercard, dominating cross-border transactions and charging substantial fees. At the same time, the use of public money, namely cash issued by the European Central Bank (ECB), is steadily declining. Cash remains the only form of money issued directly by the central bank, which guarantees its stability and privacy, but its relevance in daily transactions is diminishing as consumers increasingly rely on digital means of payment. Today, the vast majority of money circulating within the EU is private money, created and managed by commercial banks and intermediaries.

Figure 1: Share of payment instruments 2016-2022, Euro area

Source: ECB Study on the payment attitudes if consumers in the euro area (SPACE).

This shift has far-reaching implications. It challenges the ECB’s ability to maintain effective monetary control across member states and underscores the need to modernise Europe’s monetary system in response to rapid technological change and evolving consumer behaviour. At its core, every digital transaction still depends on trust, the confidence that the balance displayed on a screen can be converted into tangible, central-bank-backed cash.

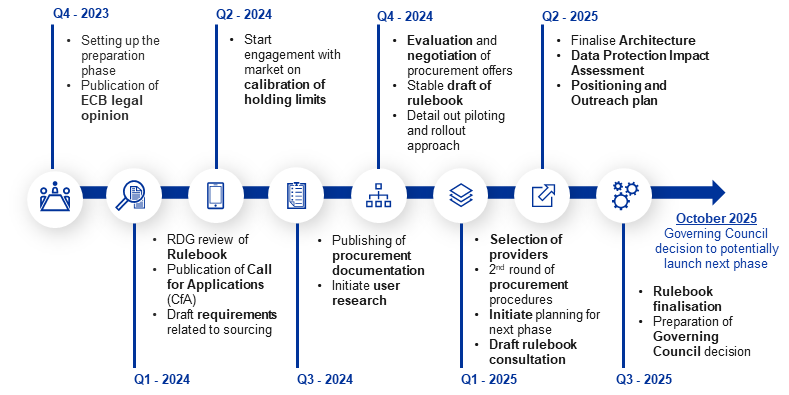

To preserve that trust in an increasingly cashless society, the ECB has been exploring the creation of a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), a new, digital form of central bank money that would coexist with cash. The final concept and implementation of this so-called Digital Euro have been under study for more than two years. Whether it should operate offline, online, or both remains under debate, with details expected in the upcoming Rulebook finalisation (Q4 2025). Back in 2023, the ECB’s Governing Council had already approved the preparatory phase of the project, while legislative implementation will depend on democratic deliberation within the European Parliament, in cooperation with the European Commission, the European Retail Payments Board, and broader civil society (ECB, 2023).

Figure 2: Digital Euro preparation phase timeline

Source: Eurosystem's digital euro project ECB

A Brief History of Money

Money has never been static. Around 5,000 years ago, early agricultural societies began replacing bartering with primitive currencies, goods like shells, salt, and metals, that held universal value. Over time, gold and silver emerged as dominant media of exchange, valued for durability and trustworthiness.

By the Middle Ages, expanding European trade brought new financial tools: bills of exchange, lending notes, and cheques. Banks in trading hubs such as Venice, Amsterdam, and London standardised currencies, safeguarded deposits, and financed commerce, laying the groundwork for the modern banking system.

The 20th century marked another turning point. The Bretton Woods Agreement (1944) tied most global currencies to the U.S. dollar, which was pegged to gold. In 1971, President Richard Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility into gold, ushering in the era of fiat money, whose value rests on government credibility rather than physical assets.

In the digital age, payments have moved online. Cryptocurrencies, launched with Bitcoin (2009), introduced decentralised alternatives, but volatility and lack of regulation limited their stability. In response, central banks began exploring CBDCs, secure, public digital currencies designed to blend innovation with monetary authority.

Benefits of a Digital Euro

From a monetary policy standpoint, the Digital Euro would preserve trust and stability by maintaining public access to central bank money in an increasingly digital society. It would also enhance the ECB’s policy transmission, ensuring a unified and efficient payment framework across all member states. As ECB adviser Jürgen Schaaf wrote, “Stablecoins are reshaping global finance - with the US dollar at the helm. Without a strategic response, European monetary sovereignty and financial stability could erode. However, in this disruption, there is also an opportunity for the euro to emerge stronger” (Schaaf, 2025).

Economically, the Digital Euro could reduce transaction costs and improve efficiency by minimising intermediary layers. The ECB’s FAQs note that it would be “free for basic use for consumers” and a “cheaper alternative to the currently fragmented payments landscape in which merchants work” (ECB, 2025b). Lower merchant fees could directly increase margins for shopkeepers and SMEs. By offering a public alternative to global card networks, the Digital Euro would enhance competition and resilience in Europe’s financial infrastructure.

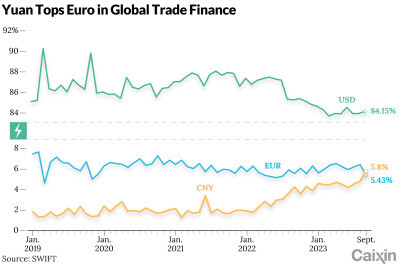

Technologically, it would encourage the growth of European fintechs and payment providers, strengthening Europe’s digital sovereignty. The Digital Euro could bolster the euro’s international role by reducing reliance on non-European systems. According to ECB data, “in the euro area, 13 countries rely on international card schemes entirely for all card transactions” (ECB, 2025a).

Enhanced interoperability across borders would further increase the euro’s appeal as a global settlement currency. Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel emphasises that “to be able to reap the benefits for cross-border payments, interoperability between CBDCs must be ensured early on” (Nagel, 2024). Such a design could make European payments faster, cheaper, and more integrated.

Costs and Political Dilemmas

Despite its promise, the Digital Euro faces economic, political, and ethical challenges. The foremost concern is privacy. Digital payments, by nature, leave a trail, raising fears of government overreach. The ECB insists that user identities will remain hidden from authorities, ensuring greater privacy than existing payment systems. Nevertheless, mistrust persists, particularly among those who fear programmable money could lead to spending restrictions.

The second issue is cost. Building a secure, interoperable system across 20+ jurisdictions requires substantial investment. A joint study by the European Association of Co-operative Banks (EACB), European Banking Federation (EBF), and European Savings and Retail Banking Group (ESBG) estimated around €18 billion in transition and implementation costs for the financial sector (Alahuhta, 2025).

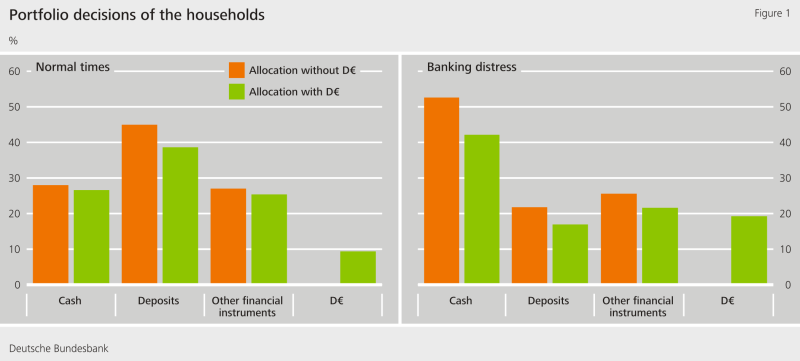

In times of financial distress, the Digital Euro could intensify liquidity strains within the private banking sector. Deutsche Bundesbank simulations show that households would reallocate a sizable share of their deposits toward cash and digital euro holdings, reducing bank deposits by over a third and diverting up to one-fifth of household liquidity. This shift would tighten funding precisely when credit support is most needed, forcing banks to rely on costlier wholesale markets or curb lending. To mitigate such risks, the ECB proposes individual holding limits of €3,000-€4,000 and non-interest-bearing balances, discouraging the Digital Euro from becoming a long-term store of value (Bruegel, 2025).

Figure 3: Portfolio decisions of households

Source: Deutsche Bundesbank Eurosystem

Ultimately, the Digital Euro stands at the intersection of technological ambition and political caution. Its success will depend on transparent governance and the ECB’s ability to balance innovation, privacy, and financial stability.

Financial Market and Macroeconomic Implications

A Digital Euro would become a new liability of the Eurosystem, circulating alongside bank deposits and cash, with broad implications for Europe’s financial architecture.

Bank funding and credit creation. ECB modelling suggests that with a €3,000 cap, the Digital Euro might absorb 2-9% of household liquid assets, depending on adoption behaviour (Lambert et al, 2023). This would represent roughly €400-1,600 billion in reallocated liquidity, non-trivial for a system where small funding shifts can move credit spreads. Mechanisms such as waterfall transfers, which automatically move excess funds back into bank accounts, would limit liquidity shocks and prevent large-scale deposit flight and bank runs.

Monetary policy transmission. A widely used CBDC could strengthen monetary policy transmission by giving citizens direct access to central bank money. Research by the BIS notes that CBDCs can “enhance the pass-through of policy rate changes to deposits and lending rates” and “increase competition and payment efficiency” (III CBDCs, 2021).

Competition and innovation. The presence of a public digital payment option would reduce the dominance of global card networks and promote competition. Beyond Europe’s internal market, the BIS highlights that enhanced interoperability between CBDCs could strengthen cross-border efficiency, reducing settlement costs and fostering faster payments.

International role of the euro. Greater global interoperability could increase the euro’s use in trade, reserves, and remittances, reinforcing Europe’s monetary autonomy in a multipolar financial world (ECB, 2025c).

Figure 4: Yuan tops Euro in global trade finance

Source: Caixin Global

Credit supply and profitability. Banks may face thinner margins if deposits decline, which would force them to rely more heavily on wholesale funding. However, most analyses, such as those by SUERF, conclude that holding caps and non-remuneration would largely leave lending activity unaffected in normal conditions (SUERF, 2024).

Anchoring Trust in the Digital Age

The Digital Euro is far more than a technical upgrade; it is a strategic evolution in how Europe defines monetary trust, sovereignty, and inclusion in the 21st century. By offering a secure, publicly issued digital payment instrument, the ECB aims to preserve confidence in money while ensuring that Europe remains competitive in an increasingly digital and geopolitical financial landscape.

Its success, however, will depend on more than code and regulation. It will require public trust, transparency, and cooperation among institutions, businesses, and citizens. If executed wisely, the Digital Euro could strengthen the euro’s global position, deepen European integration, and anchor the continent’s monetary sovereignty in the digital age.

References

Alahuhta, A. (2025, June 17). How much would the digital euro cost? | Finanssiala. Finanssiala. https://www.finanssiala.fi/en/news/how-much-would-the-digital-euro-cost-initial-estimation-published/

Chinese yuan edges out euro as Second-Most used currency in global trade finance. (2023, October 31). Caixin Global. https://www.caixinglobal.com/2023-10-31/chinese-yuan-edges-out-euro-as-second-most-used-currency-in-global-trade-finance-102122297.html

European Central Bank. (2023, January 23). The digital euro: our money wherever, whenever we need it. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2023/html/ecb.sp230123~2f8271ed76.en.html

European Central Bank. (2024). Progress on the preparation phase of a digital euro - First progress report. European Central Bank. https://doi.org/10.2866/10580

European Central Bank. (2025a, February 28). Most EU countries rely on international card schemes for card payments, ECB report shows. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2025/html/ecb.pr250228_1~7f0697af45.en.html

European Central Bank. (2025b, July 16). FAQs on a digital euro. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/digital_euro/faqs/html/ecb.faq_digital_euro.en.html

III. CBDCs: an opportunity for the monetary system. (n.d.). https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2021e3.htm

Lambert, C., Larkou, C., Pancaro, C., Pellicani, A., Sintonen, M., & European Central Bank. (2023). Digital euro demand: design, individuals’ payment preferences and socioeconomic factors. In ECB Working Paper Series (No. 2980). https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2980~5f64961c8f.en.pdf

Nagel, J. (2024, October 14). Joachim Nagel: Introducing a digital euro - the cross-border dimension. https://www.bis.org/review/r241014i.htm

On the digital euro holding limits. (2025, May 28). Bruegel | the Brussels-based Economic Think Tank. https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/digital-euro-holding-limits

Schaaf, J. (2025, July 28). From hype to hazard: what stablecoins mean for Europe. European Central Bank. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2025/html/ecb.blog20250728~e6cb3cf8b5.en.html

SUERF. (n.d.). SUERF. https://www.suerf.org/publications/suerf-policy-notes-and-briefs/a-digital-euro-monetary-policy-considerations/

Will the digital euro strengthen financial stability? Yes, within certain limits. (n.d.). https://www.bundesbank.de/en/publications/research/research-brief/2024-66-digital-euro-financial-stability-665792

Link 1 ; Link 2 ; Link 3 ; Link 4 ; Link 5 ; Link 6 ; Link 7 ; Link 8 ; Link 9 ; Link 10 ; Link 11 ; Link 12 ; Link 13 ; Link 14 ; Link 15 ; Link 16